hello!

welcome back to i was cooking. you’ll notice that there’s a new look to the newsletter both here (ahem, banner image) and on social media. this bout of creative energy is fueled by my last 4 months of travel (7 countries, 12 cities, not including coming back to boston a couple times) as well as my current joblessness, which is allowing me plenty of idle time to stress, pitch to magazines, fill out job applications that tbh could’ve been a first interview instead of a long google form, and furiously write this newsletter so i can exclaim “well at least i’m doing SOMETHING” every few minutes to no one in particular.

today’s issue is actually a piece i already wrote for salt & pepper magazine last fall. i made olivia take tons of photos of me with the physical magazine last year and then immediately forgot to post about any of it. the girl stood in the rain while taking them—the least i can do is actually post them.

this personal essay marked a big milestone for me: it was the first time i’ve ever been paid for my writing. while the sum was modest, it felt special to see my idea develop from pitch to finished work, receive the physical magazine in the mail with my name in it (and some gorgeous illustrations accompanying my work), and then receive a payment on paypal for my writing. i hope i can experience the feeling again, and if you see any open calls for food and travel mags, please send them my way.

if you’ve ever joined me for a meal, this one’s for you :)

from baghdad, with lamb

originally published with Salt & Pepper Mag for the Spice Issue

Growing up in Baghdad’s Armenian community meant that there was never a shortage of food or family to share it with. Even in the years following the US invasion of Iraq in 2003, when we lived in fear and uncertainty, my family never missed the chance to celebrate a birthday, wedding, or religious holiday. And what better way to show love, resilience, and resistance to hopelessness than through a dinner party?

Ever gregarious, my stepmom would mark the occasion with a lavish dinner: a spread of homemade creamy hummus, mutabbal that stunk up the house with the scent of burnt eggplant skin, fattoush sprinkled with the crispiest pita, and bright green tabbouleh; for the main course there was festive yellow saffron rice adorned with jewel-like purple raisins and gleaming fried slivered almonds and quzi, an Iraqi lamb dish simmered in warm spices for hours till the meat becomes meltingly tender. For dessert, we often had an impressive tower of croquembouche and a perfectly browned-but-not-burnt crème caramel. These complex French desserts were all the rage at the time, served alongside store-bought baklava and tiny glasses of bitter black tea.

This meal would take her two days of stress and short-temperedness to prepare, but when all was said and done, she stood at the center of attention, doling out heapings of this masterpiece she’d laboured over alone, being showered with praise, graciously denying any of it was a great effort. As an eight-year-old, I was dazzled by these displays of care and extravagance. Cooking took on a mythic status–it felt like my birthright and my future, that certainly, obviously, I would grow up to entertain just as the women in my family did.

But when I went into the kitchen, following my mom or grandma around with questions and requesting to help form the kubba or wrap grape leaves around rice and spiced ground beef for dolma, I was repeatedly dismissed. No one seemed to think that educating me on cooking was of great concern. I didn’t learn how to cook till I got married, the women assured me, I had to call my mom every day and she’d teach me to make dinner over the phone. The proof was in the pudding: my unmarried aunt and newly-wed aunt-in-law had no clue what they were doing in the kitchen, and spoiled little me refused to eat the dishes they were experimenting with.

My questions kept piling up. Why are you using fennel instead of cumin? What’s the proportion of ground beef to rice flour in kubba hameth? How do you know how much spice to add if you’re not using teaspoons to measure? In high school in much-safer Armenia, I started baking American desserts, which seemed like a territory I could control, knowing my mother would never be interested in these foods. I started asking my parents for ceramic pots and specialised baking equipment, but these requests were met with the most perplexing response: we can get those for you when you’re married. Maybe they were trying to brush off my requests, but I was deflated. I didn’t want to marry. And I didn’t want to cook just to feed a man. Why wasn’t this a skill I could attain for myself? Despite being a hardheaded, un-nuanced teen feminist at the time, I didn’t blink twice when I threw myself into the kitchen, adamant to harness the secrets of my mom’s spice cabinet.

First, her cabinet was indecipherable. Some spices were in washed and repurposed Nutella jars, with a piece of paper taped to them declaring the contents within in my mom’s dainty Arabic script. Some labels also boasted the spice’s Armenian name so she knew how to ask for them in Yerevan’s supermarkets. Some were labelled in English if it was a spice a relative had sent her from the US or England. Worst of all, the baking ingredients were in their original packaging, all in Cyrillic, as much of Armenia’s packaged food comes from Russia.

To learn, I watched my mom cook. I went into the kitchen when she wasn’t working and sniffed all the spices, trying to put smell to sight. I tried to impose my own order on the spice cabinet, first by alphabet (which didn’t work out since everything was labelled in a different language) and then by colour. Clearly, I wasn’t being attentive when watching her–when my mom cooked, she knew the spices by sight and spot in the cabinet–she relied on muscle memory to reach her familiar favourites. My terrible organisation system meant she had to go in and undo my work, and I learned real fast to not backseat cook.

When I left Armenia for Emerson College in Boston, I was determined to have my own perfect, organised spice cabinet. I was so eager to get away from the rigid norms of home, to be anonymous in a new city where I had no family, that I was willing to shed my cultural identity in exchange for this newfound independence.

In the Star Market in downtown Boston, I found spices packaged in ways that I’d never witnessed before: neat, identical jars with neat, identical illustrations and legible names, organised alphabetically in a dispensing rack. Eager to expand my palate beyond the Arab dishes I’d grown up with, I looked past the familiar spices my mom always stocked and reached for the oregano, crushed red chili flakes, paprika, and cinnamon. Judging by how these are usually the only ones sold in larger containers, I guessed that they were the main spices used in American cuisine.

But by my junior year, things weren’t going according to plan. In my dorm’s small shared kitchen, the more I cooked, the more I noticed my desperate need for deeper flavour and bolder spice. Sure, the chicken piccata and quinoa with kale and sheet pan cod with roasted vegetables made for good meals, but I couldn’t shake the feeling that the things I was making tasted so drab.

At the supermarket, my eyes began to wander to find the old friends I’d left behind: cumin, clove, allspice, fennel seed. I found sumac and zaatar at an Arab grocer near my college, nearly crying when I first saw them–I didn’t realise how much I’d missed them after a two-year absence. The change happened without me noticing it. Suddenly, the chicken piccata was replaced with floral djaj may narenj, a dish made out of chicken that’s simmered in a rich, yellow saffron stew with cardamom, orange blossom water, and potatoes, and so perfectly incorporates all the flavours of my childhood. The kale and quinoa were sometimes substituted with sour chard and nutty bulgur. The cod was rubbed with olive oil and herby zaatar, while the roasting vegetables got a sour kick from a sprinkle of burgundy sumac.

Now, when I visit my parent’s home in Armenia, I no longer feel like a child watching my mother make magic in the kitchen but rather like a seasoned cook following along her process. I know now that using teaspoons to measure out your spices only slows you down, and that a lot of spices can be omitted or substituted when you don’t have them on hand. I understand why my mom only bought what she needed when she needed it, since spices have a shelf life of about a year before losing potency.

In my own kitchen in Boston, I’ve become the dinner party host I always wanted to be: executing dishes that show care to my guests while making everyone feel like they have contributed to the party. True to my mission to carve out my identity away from home, I’ve chosen to not cook alone (unlike my mother). Instead, I delegate dishes and ask for help in the kitchen. The end result means that the dinner table is less unified thematically, but is more representative of us as a friend group. When you ask everyone to contribute, you end up with a table showcasing everyone’s talents.

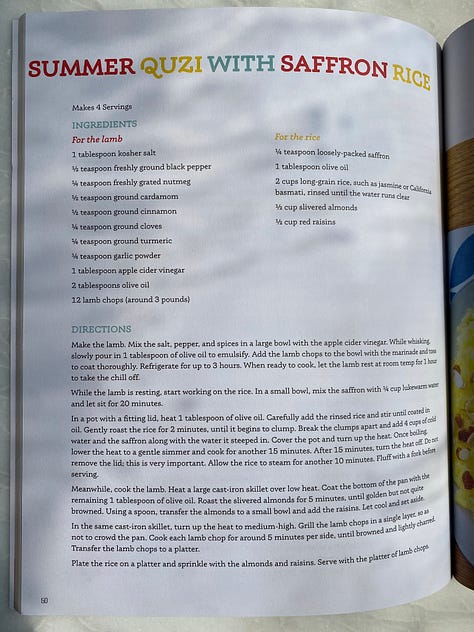

summer quzi with saffron rice

Ingredients:

For the lamb

1 tablespoon kosher salt

½ teaspoon freshly ground black pepper

¼ teaspoon freshly grated nutmeg

½ teaspooon ground cardamom

½ teaspooon ground cinnamon

¼ teaspoon ground cloves

¼ teaspoon ground turmeric

¼ teaspoon garlic powder

1 tablespoon apple cider vinegar

2 tablespoons olive oil

12 lamb chops (around 3 lb)

For the saffron rice:

¼ teaspoon loosely packed saffron

2 cups long-grain rice, such as jasmine or California Basmati, rinsed until the water runs clear

1 tablespoon olive oil

½ cup slivered almonds

½ cup red raisins

how to

Mix the salt and spices in a large bowl with the apple cider vinegar. While whisking, slowly pour in 1 tablespoon of olive oil to emulsify.

Add the lamb chops to the bowl with the marinade and toss to coat thoroughly. Refrigerate for up to 3 hours. When ready to cook, let the lamb rest at room temp for 1 hour to take the chill off.

While the lamb is resting, start working on the rice. In a small bowl, mix the saffron with ¼ cup lukewarm water and let sit for 20 minutes.

In a pot with a fitting lid, heat 1 tablespoon of olive oil. Carefully add the rinsed rice and stir until coated in oil. Gently roast the rice for 2 minutes, until it begins to clump. Break the clumps apart and add 4 cups of cold water and the saffron. Cover the pot and turn up the heat. Once boiling, lower the heat to a gentle simmer and cook for 15 minutes. After 15 minutes, turn the heat off. DO NOT REMOVE THE LID and allow the rice to steam for another 10 minutes. Fluff with a fork before serving.

When you’re ready to cook the lamb, heat a large cast-iron skillet over low heat. Lightly coat the bottom of the pan with the remaining 1 tablespoon of olive oil. Roast the slivered almonds for 5 minutes, until golden but not quite browned. Using a slivered spoon, transfer the almonds to a small bowl and mix with the raisins. Let cool and set aside.

In the same cast iron, turn up the heat to medium-high. Grill the lamb chops in a single layer, around 5 minutes per side. This may need to be done in 2 batches. Transfer the lamb chops to a platter, and serve warm.

Transfer the rice to a second platter, and sprinkle with the almonds and raisins. Serve.

this essay + recipe was originally published with Salt & Pepper Mag for their Spice Issue in fall of 2022. All illustrations + photos in the magazine itself are courtesy of the publishers. Much thanks to Carlo for bringing this pitch to life :)